[ad_1]

When Y2K appeared just like the world’s most urgent technological concern, the Mexican-Canadian artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer was utilizing a dictionary and a set of grammatical guidelines to show a pc the best way to write questions. This system he constructed could make enquiries in Spanish, English, German and French, in 4.7tn attainable combos. When the art work confirmed on the San Francisco Museum of Fashionable Artwork final yr, it nonetheless had 271,000 years of latest inquiries to ask.

Which is to say, Lozano-Hemmer has been working with generative know-how lengthy sufficient to have realized a strong lesson: “There isn’t a such factor as a impartial algorithm.”

This lesson was reiterated to the Bafta-winning media artist in a spectacular, humiliating style at Miami Artwork Basel slightly over a decade in the past. It was his first time utilizing facial recognition know-how, nonetheless nascent on the time, in an art work: The 12 months’s Midnight would present viewers a projection of their face on a display, then snatch out their eyeballs, leaving plumes of smoke wafting from the sockets.

“It was working tremendous,” Lozano-Hemmer says, till Sean Combs – the rapper variously referred to as Puff Daddy, P Diddy, or Diddy – stepped as much as strive it. The facial recognition tech merely couldn’t find Combs. “He took off his glasses, which is a giant deal,” Lozano-Hemmer says. “Early variations of face detection trusted distinction with a backdrop. And the backdrop was black.” Combs found out the issue as shortly as Lozano-Hemmer did: “He was like, ‘That is racist’.”

(From that second on Lozano-Hemmer and his programming workforce developed extra sturdy methods to check their artworks.)

Anybody fiddling round with ChatGPT as of late have to be cognisant of AI’s biases, he says. “You could preserve all the time underlining to your self that you just’re working with a set of choices and prejudices that had been made on the time of coding,” he says, including: “The know-how is getting higher … then again, higher for whom?”

“Higher for whom?” is precisely what Lozano-Hemmer hopes folks will ask as they wander by means of Atmospheric Reminiscence, his new exhibition at Sydney’s Powerhouse museum: a present that required greater than 60 folks, from eight totally different nations, to mount. It’s best described as an immersive exhibition, however Lozano-Hemmer is effectively conscious of the luggage that phrase comes with. “I can’t stand that shit,” he says of projection-based exhibitions, “the place you’re presupposed to go in there and really feel such as you’re at one with nature, otherwise you’re seeing once more the work of those previous masters”.

The centrepiece of Atmospheric Reminiscence is Subject Atmosphonia, an unlimited, velvet-dark room the place guests wander beneath 3,000 audio system, every one ringed with twinkling lights and taking part in a person field-recording. It options 300 species of fowl track, which transition into bushfires and crashing waves; a cacophony that hits you at full-force, proper between the ears.

“As you stroll round, you create a story out of the three,000 recordings,” Lozano-Hemmer says. Because the audio system activate, the viewer is bathed in a transferring halo of sunshine. However behind the scenes: “It’s a nightmare – it’s acquired, I feel, 32km of cable.”

The present’s premise stems from a paragraph within the Ninth Bridgewater Treatise, written by the computing pioneer Charles Babbage in 1837. Babbage proposed that the air surrounding us might be a “huge library” that, as soon as attuned to correctly, might supply good recollection, capturing each motion, second and utterance ever handed. This notion is “very romantic and exquisite,” Lozano-Hemmer says, “however it’s a very dystopian mission.”

Within the exhibition’s first room, the core of certainly one of Babbage’s mechanical calculators, Distinction Engine No 1, is on show. The Powerhouse curator Angelique Hutchinson says wanting on the steampunk machine, concerning the dimension of a shoebox, could be an existential expertise. “It’s fairly humble,” she says. However while you replicate on the predictions Babbage made, a lot of which got here to move, “it causes you to consider the place we’re going to go subsequent”.

Close by is a collection of dialog cubicles constructed by Lozano-Hemmer, the place guests can sit and watch the phrases from their mouths remodeled into textual content as they converse. No matter they are saying will likely be answered by a digital incarnation of Babbage, skilled on the pc scientist’s texts, and powered by OpenAI, the know-how behind ChatGPT.

Lozano-Hemmer believes there are three human qualities that know-how won’t ever be capable of replicate: we are able to improvise, we are able to neglect and, maybe most significantly, we are able to die.

These concepts are interwoven into Atmospheric Reminiscence, an interactive exhibition that is determined by human improvisation. “It’s fairly boring with out folks,” he says, as we stroll by means of the largely-empty exhibition house collectively.

Machines are additionally “actually good at remembering” – a spoiler for the dystopia to return – and as for loss of life, it’s in every single place. When unattended by a dwelling particular person, the interactive works often generate textual content or motion on their very own – “possessed” by Charles Babbage, a ghost within the machine.

The avant garde accordionist Pauline Oliveros, who died in 2016, additionally makes a posthumous look within the present: earlier than she died, she exhaled into a tool which now circulates her breath between a bellow and a brown paper bag.

In watching Oliveros’ “Final Breath” going out and in, you’re “observing the fleeting time that we’re right here and the fragility of that bag,” Lozano-Hemmer says. He chases that existential remark with one other perception: if it weren’t completely aspirating air from a lifeless artist, the bag could be used for fried rooster. That’s the perfect variety to seize breath, he says, as a result of it’s “lined with plastic, for the juices”.

after newsletter promotion

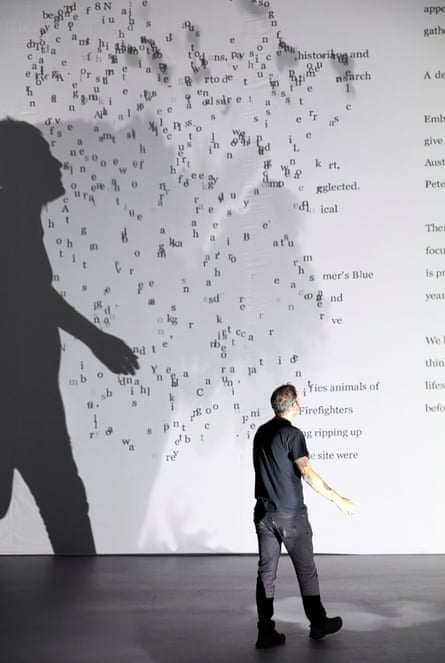

The climax of the show is Atmospheres, a “projection chamber” that takes up the museum’s lofty 11m walls, and all 252sm of its floor space. As with the rest of the show, moments of spectacle and opportunities for self-regard are everywhere. A shadow-play allows viewers to see their silhouettes scaled up and projected over giant pages of text. As they move, their body heat evaporates the words around them. “Kids just love to play with this,” Lozano-Hemmer says.

Another work lets viewers speak into a microphone and see their utterance transform into a literal text cloud, made of cold water vapour. When the work debuted in Manchester in 2019, “People were like, ‘fuck Brexit’,” Lozano-Hemmer says. “They were just speaking their mind. The piece does not censor. It writes anything that you say to it.”

The work has subsequently been modified for Australian audiences – not to limit locals’ expansive capacity for foul language, but to better comprehend it. The artwork is powered by Google’s transcription engine, and since switching it over to Australian English, “we’ve noticed a big improvement. It really understands Australians.”

Towards the end of the cycle, the whole room crashes. We are presented with Babbage’s hope for his “vast library” in the air – that it could reveal past misdeeds, and bring slave owners to justice – which is followed by what Lozano-Hemmer says is the rallying call of our time: “I can’t breathe.”

The projections suddenly turn inward, showing CCTV footage of the room itself. This is Zoom Pavillion, a 2015 work made in collaboration with the Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko. Viewers now see themselves on screen, not as stars but as targets. The technology that seems so entertaining can just as easily be used to capture, classify and control.

From there, it gets worse. A random visitor who shared a booth with Babbage at the beginning of the exhibition will see their face blown up, in close up, across the full height of the room.

That face is joined by more and more images of exhibition attendees, all logged and remembered – because computers do not forget. It is disturbing to witness, even if your face isn’t up there. “Even if you don’t see yourself, you understand that the spirit of this project is that all of this comes at a cost,” Lozano-Hemmer says.

For me, Lozano-Hemmer’s work brings to mind Arthur C Clarke’s third law: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” At first, his art dazzles. But just like when a magician’s secrets are revealed, there is a point when it no longer seems magic – you just feel tricked. And that moment is the point, he says, where you realise “you are the content … where all of the different technologies that have been used for simulation of this environment can be seen for what they are”.

Babbage wasn’t wrong about the air around us being a recording device, Lozano-Hemmer says. “What is atmospheric memory? Well, the memory of industrialisation that Babbage helped automate is this carbon dioxide that is currently increasing. The atmosphere has been colonised by drones, which are bombing people right this minute. It is the site for oligarch networks of power and control.

“What can we do, other than make evident these mechanisms, to reclaim the atmosphere as a site for song and community, as a site for poetry and engagement?”

In the hopes of answering that question, Lozano-Hemmer has added a denouement to the dystopia.

Instead of being shattered then spat out into the gift shop, visitors walk from the projection chamber into a sort of decompression room: a library lined by archival posters from Australian protest movements, with books on the climate crisis, surveillance capitalism, and Indigenous knowledge systems, with spaces to sit, read and breathe.

“The artwork needs to be directing all of that emotion into something that can be practical,” Lozano-Hemmer says, adding: “We don’t tell you what to think or not to think. We let interaction generate the conditions for change.”

[ad_2]

Source link