[ad_1]

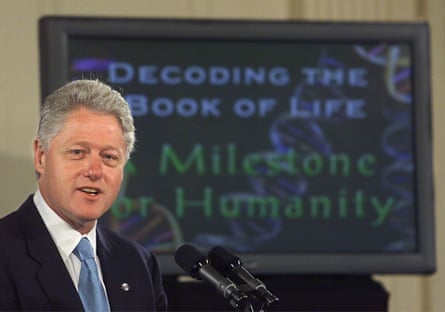

In June 2000, Invoice Clinton, the then US president, stood smilingly subsequent to the leaders of the Human Genome Mission. “In genetic phrases, all human beings, no matter race, are greater than 99.9% the identical,” he declared. That was the message when the primary draft of the human genome sequence was revealed on the White Home.

The one string of As, Ts, Cs and Gs finally turned the primary human reference genome. Since its publication in 2003, the reference has revolutionised genome sequencing and helped scientists discover 1000’s of disease-causing mutations. But at its core is a considerably ironic drawback: the code meant to characterize the human species is generally primarily based on only one man from Buffalo, New York.

Although people are very related, “One particular person isn’t consultant of the world,” says Pui-Yan Kwok, a specialist in genome evaluation primarily based at College of California, San Francisco and Academia Sinica in Taiwan. In consequence, most genome sequencing is basically biased.

This bias limits the sort of genetic variation that may be detected, leaving some sufferers with out diagnoses and doubtlessly with out correct remedy. What’s extra, individuals who share much less ancestry with the person from Buffalo will most likely profit much less from the incoming period of precision drugs, which guarantees to tailor healthcare to people.

To fight this, researchers have began to assemble reference genomes for particular international locations, together with South Korea, Japan, Sweden, Denmark and the United Arab Emirates. They hope it will serve their populations higher, however critics fear it may flip migrants into second-class residents of their healthcare techniques. Now, an enormous new mission is providing a distinct resolution with the goal to characterize world range: a human pangenome.

Precision drugs, also called personalised drugs, has been a buzzword throughout the medical group for years and it undeniably sounds good. “Getting the appropriate drugs to the appropriate affected person on the proper time is the tagline,” says Neil Hanchard, a doctor scientist on the US Nationwide Human Genome Analysis Institute.

However commonplace genome sequencing misses lots of variation that could possibly be related to illness. Most often, it really works by chopping DNA into small bits generally known as “brief reads”, earlier than sequencing them and organising them right into a genome utilizing the reference as a information.

Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) – a change from a C to a T within the code of a gene, say – are largely simple to identify this fashion, however bigger chunks of variation generally known as structural variants (SVs) are trickier. New sections, typically a whole lot or 1000’s of base pairs lengthy, can go undetected, as can sections which might be lacking, reversed or moved some other place. In these circumstances, brief reads can not simply be mapped to the reference and “an entire bunch”, says Kwok, are thrown away.

Which means that commonplace genome sequencing is biased in direction of the SVs already within the reference. In case your SVs differ, you find yourself with a sequence that doesn’t absolutely seize your private variation. As it’s these small variations between those who we hope will inform us, for instance, why one particular person may reply effectively to a medication however one other particular person is not going to, that’s unhealthy information.

Kwok’s work hints on the quantity of SVs going undetected. In 2019, his group analysed samples from 154 individuals around the globe and located 60m base pairs-worth of SV genome content material lacking from the reference, with rather more nonetheless on the market. A follow-up of 338 those who appeared just for additional inserted DNA discovered almost 130,000 new sequences.

However SVs additionally seem to indicate completely different frequency patterns in several populations. By extension, says Kwok, if an individual “is from a inhabitants fairly completely different from the particular person from which the genome reference is derived, there can be extra misalignment” when their brief reads are mapped to the reference. Consequently, he says: “We might miss danger variants in these areas not represented within the reference.”

This lack of illustration is a normal drawback in genomics. Even the extra studied SNVs present giant knowledge gaps. Not too long ago, for instance, Hanchard and his colleagues sampled 426 people from 50 ethnolinguistic teams throughout Africa and located greater than 3m new SNVs, largely from populations that had by no means been sampled earlier than. “We haven’t even touched [SVs],” says Hanchard, “however our preliminary knowledge suggests it’s going to be extra of the identical.”

Such knowledge disparities immediately have an effect on medical outcomes. For instance, if an individual with a uncommon variant has a uncommon illness, there’s a good probability the variant is accountable. However usually we have no idea whether or not variants are genuinely uncommon, or simply widespread in understudied populations. In these circumstances, medical doctors can not give a prognosis. “For individuals with non-European ancestry, that happens much more,” says Hanchard.

As we transfer into an period of precision drugs, that may solely develop into extra vital. Kári Stefánsson, whose Reykjavik-based biotechnology firm DeCode Genetics specialises in connecting the dots between genetic variants and illness, says that what retains him up at evening is that our understanding of range inside populations of European descent is now so good that we will begin to use it for precision drugs. However for different populations, “We should not have the identical sort of knowledge,” he says. “[This] goes to extend healthcare disparities above and past what they’re immediately.”

While there are not any genetic underpinnings that meaningfully group individuals into completely different races, some consider it is sensible to create references to seize the variation inside particular populations, equivalent to ethnic teams and nation states. One nation that now has its personal reference is Denmark.

“What we see is that there’s lots of variation that [has only been detected in] the Danish inhabitants,” says computational biologist Simon Rasmussen of Copenhagen College, who led the work. That could be a robust argument for an area reference, and the attraction is clear: a reference primarily based on Danes is uniquely positioned to supercharge the Danish healthcare system.

However some criticise nationwide genomes for focusing an excessive amount of on variations between populations, reasonably than people. Medical anthropologist Emma Kowal of Deakin College in Victoria, Australia, worries that nationwide genomes may “maintain the thought of race alive”. And framing genomes when it comes to nationality does inevitably result in exclusion, says Jenny Reardon, a sociologist of the life sciences primarily based on the College of California, Santa Cruz. “We’re deciding, in impact, who’s Danish and who isn’t.”

Rasmussen admits the reference can be much less helpful for the 15% of the Danish inhabitants who’re migrants or their descendants. Samples from individuals with blended ancestry had been even eliminated in the course of the choice for the reference. However due to consent issues the reference by no means made it to the clinic, so Rasmussen and his group need to create one other. For that, he says: “We need to take a distinct [selection] strategy.” Precisely how is but to be decided.

There may be an alternative choice to the nationwide genomes, although. As an alternative of zooming in on completely different populations, the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium needs to zoom out; overlaying many genomes to create a reference that has variation constructed into it – a pangenome. The consortium not too long ago printed the primary draft of such a reference in a preprint.

Made up of 47 exquisitely detailed genomes, the draft represents the primary chunk of the 350 genomes it’s planning to sequence to incorporate the most typical variation the world over. “This isn’t an ordinary that has ever been carried out earlier than,” says Karen Miga of the College of California, Santa Cruz, who’s a part of the consortium.

However the mission is not only about sequencing extra various knowledge. “We have to give you a greater knowledge construction to encode that data,” says Miga’s colleague Ting Wang of Washington College Faculty of Medication in St Louis, Missouri.

That knowledge construction is known as a genome graph. In distinction to the present reference, which is only a lengthy string of letters, the genome graph exhibits variation between genomes as detours on an in any other case shared path. That may allow researchers and medical doctors to map brief reads to the model of the trail that most closely fits their pattern.

The pure query is: how does one select who will get to characterize the world? The primary genomes certified due to their excessive technical high quality, however the consortium might want to select new samples in future. Since Africa is the cradle of humanity, Miga says: “The overwhelming majority of the genomes that we’re together with are of African ancestry.”

From Reardon’s perspective, nevertheless, 350 individuals may do a greater job of representing the world than one particular person, however “[the consortium] have made some decisions about teams,” she says. “Who did they pattern? Who did they not pattern?” So long as the reference incorporates solely a subset, arguably somebody is not going to make the minimize.

Miga doesn’t deny that. “[We are] actually making an attempt to seize widespread variation at a world degree, so stuff you would see fairly regularly,” she says. Documenting widespread variation on this case leaves out unusual variation. “Should you’re in search of one thing extraordinarily uncommon,” she says, “that isn’t our cost in the mean time.”

In an excellent world, people would have their genomes sequenced with out using a reference. This has lengthy been held up as the last word, problem-free resolution, however hardly anybody believes that’s on the playing cards. “It’s not a trivial endeavor and I don’t see it being non-trivial in 10 years’ time,” says Hanchard.

And reasonably than utilizing a broad, world pangenome, international locations may be swayed by a reference extra tuned to their inhabitants, in addition to maintained and managed by themselves. “We don’t actually count on anybody apart from the Danes to make a Danish reference genome,” says Rasmussen, who hopes the following iteration can be run by Denmark’s state-controlled Nationwide Genome Centre, doubtlessly as a part of the EU’s Genome of Europe mission.

Hanchard additionally sees the advantage of native or regional references. “[The pangenome] isn’t going to have all of the variation represented,” he says. He’s a part of the H3Africa consortium, which goals to deliver the advantages of genomics to Africa and is contemplating an Africa-specific genome graph. On the similar time, he expects all these references will most likely finally coalesce.

When requested about his hopes for the way forward for genomics, he speaks of figuring out and understanding the variation because it pertains to himself, or anybody else with Jamaican ancestry. “I’d like to get to a degree the place everybody feels represented and that that is for them, as a lot as it’s for any explicit group,” he says. “We’re from one humanity, that’s the vital half.”

[ad_2]

Source link